Another day, another megadollar acquisition. But what is the end goal here, and how might Evolution realise the synergies? Kevin Dale from Egamingmonitor.com takes a look at the history of gaming M&A and whether the old guard might have something to share with this relative newcomer.

No sooner does NetEnt acquire Red Tiger than they in turn get gobbled up by Evolution. Most of us were expecting the first acquisition to take months, if not years, to assimilate but it seems that a relative newcomer to the gaming space has a healthy appetite to match its Pacman-shaped logo. Let’s hope their digestive tract is up to it.

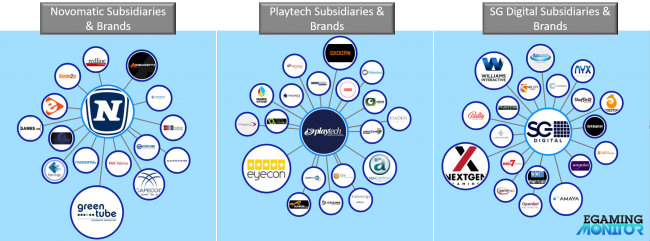

Multiple or mega acquisitions in our sector are nothing new. Of the 1,000 companies on the supply side of our industry, around 20% are subsidiary companies and/or brands. Three of the largest groups in our sector have around 15-20 brands under their tight waistbelts.

Most of these are the result of acquisitions up and down the value chain and across product lines. Given their history of absorbing companies, what integration templates might Evolution adopt from these multi-pronged goliaths of old?

Taking a look below at what remains of subsidiary brands and how they are used, you get an idea of how acquisitions have been assimilated.

Novomatic

Of 16 Novomatic subsidiaries in the online gaming space, 11 still operate separate websites, suggesting, perhaps, a decentralised approach to M&A. Meanwhile, half of all brands are still used for launching new content.

Ainsworth, their largest purchase, is only a partial acquisition (52%) and so you’d expect some cross-selling synergies but limited integration. At the other extreme, a couple of old gaming brands such as Igaming2go and Redline Games are dormant.

However, some wholly owned brands, acquired many moons ago, are still used in the marketplace. As well as marketing games through the group brand Novomatic (especially for offline products), a handful of online brands, such as Greentube, Capecod and Eurocoin (plus Funstage, Cervo & Bluebat on the social front) are retained.

Playtech

Of 20 or so subsidiaries in online gaming, seven still have live websites but 10 are used as product brands. Game brands which ‘live on’ include Eyecon, Quickspin, Sunfox and Ash, whilst others are either dormant or ‘quiet’, such as Viaden, Geco and Rarestone.

Interestingly, Playtech has launched a couple of new in-house studio brands recently (created by design rather than via acquisition) including Playtech Origins and Playtech Vikings. This is a clear signal that the company is comfortable with the idea of a multi-brand strategy for studio content.

Scientific Games

Of 20 subsidiaries, only seven retain websites but a whopping 12 separate game brands are used for marketing games.

As a studio/aggregator hybrid, the company’s range of studios is flattered by the existence of so many in-house ‘studios’: Bally, Barcrest, Betdigital, Game360, NYX, NextGen, Openbet, Red7, Shuffle Master, SG, Side City and WMS.

Lessons from the big boys

So, what might Evolution or others glean from the integration efforts above? Despite the higgledy-piggledy mix of complete and partial assimilation above, there seems to be a high amount of consistency in approach here – or at least some consistency to their inconsistency!

The big boys have all wrestled with post-merger integration (PMI) issues and that awkward compromise of integration + laissez faire may be the result. How far and how fast to assimilate has a few component parts:

- Will speed of integration improve bottom line profitability? And at what short-term cost?

- Which parts of an acquired business, such as the brand, can be usefully retained?

- What synergies were expected, or can be realised from the acquisition/merger?

Fast and furious or softly, softly?

Assets take time to integrate and while some business texts might suggest a big bang, no-pain-no-gain approach, often that’s not an option. Earn-out fees may require separate profit and loss for a period, staff morale always plays a part, and many under-estimate the market sentiment for acquired brands. The sheer time it takes to integrate or migrate tech platforms (without losing customers) is not for the faint hearted. There are plenty of valid reasons for those speedy integrations to hit the buffers.

The process is complicated too by the nature of product lines involved. The more disparate the businesses, the more difficult they are to integrate. Digesting Ezugi, another live dealer, is one thing but NetEnt (plus Red Tiger) is a different scenario.

Where 2+2 > 4

Then there’s the question of which assets and teams should be retained – or not. Headcount reduction is an expected consequence of M&A, especially in roles where duplication exists. But the extent of duplication itself is a function of how far you intend to combine the two entities.

Cost synergies are trumpeted as a justification for acquisitions so if you do not make cuts, you may be asked why. At the other extreme, the complete assimilation of assets can lead to an amorphous group which loses focus on individual product lines or customer groups. Moreover, without some devolved P&L responsibility, corporate largesse and bureaucracy can more than offset any cost savings.

Having gone all-in on integrations, some firms later spin out business units from their core, whilst retaining ownership. This can rejuvenate subsidiaries allowing them scope to hone their own products and to innovate, whilst still benefiting from the umbrella services of the group, such as compliance and finance.

Multi brand versus multi studio strategies

Launching new products under an old brand or retaining old websites does not necessarily mean that the studio behind it has survived in its original form. Some subsidiaries are phased out completely, others live on as hollow brands for marketing purposes, whilst a handful are maintained as semi-autonomous studios within the group.

Hollow or not, many firms take a multi-brand approach for good reasons:

- There is a useful separation between platform brands and studio brands. Third party aggregators are more likely to add a studio such as Bgaming to their roster rather than a competing platform provider such as SoftSwiss;

- Similarly, other studios are more likely to do a distribution deal with an aggregator brand such as 1X2 Network, rather than with a competing studio such as Iron Dog;

- Different brands can also focus on different product or customer types: slots vs table games vs virtual games vs video-bingo etc; offline vs online games; branded vs non-branded; localised vs non;

- Exclusive deals can be made with operators that cover one studio (rather than all content)

- Both operators and aggregators like to publicise the number of studios and the number of games they can offer. A multi-studio approach sells well here, especially if each ‘new’ studio doesn’t require a separate integration;

- On operator sites where games can be filtered by brand, a multi-brand supplier has more chance of retaining end-users who ‘switch’.

One downside of multi-brand strategies is that marketing spend is dissipated and so creating brand awareness is more difficult. That said, we are talking B2B brands here, where those who matter are easier to identify and target one-on-one.

Microgaming has taken the multi-brand strategy to a whole new level, launching 10 new and ‘independent’ studios, such as Gameburger, All41 and Neon Valley. Whilst the extent of their independence is unknown, you would expect to see separate offices, budgets and reporting structures for real autonomy to bear fruits. A multi-brand strategy is very different to a multi-studio one.

A vision for achieving more than the sum of the parts

The recommendation by NetEnt to accept the Evolution offer came with some vague sounding synergies such as “becoming the world leader”, “best in class”, “combined portfolio” etc. The bid for NetEnt values the company at around £1.6bn, representing a premium on existing shares of 43%. This is a massive windfall for NetEnt shareholders – and who can blame them for taking the deal.

But if they’re in it for the long term, these shareholders do need a vision of what the end goal looks like. What are the specific synergies and what approach can staff and shareholders expect? The same goes for staff on both sides too, as they are key to realising any PMI benefits. Where will the group end up on that continuum from: a lean, highly integrated entity to a somewhat looser, devolved harmony of business units?

Deloitte quotes a numbing statistic: “empirical studies indicate that one of every two PMI efforts fares poorly.” So a bit of clarity is probably welcome.

Kevin Dale is the co-founder of Egamingmonitor and CEO of Farawaysports. He was previously CEO of Gameaccount (now GAN plc) and CMO at Eurobet, Sportingbet and Betfair.

Egamingmonitor.com is an advisory firm to the gambling industry, with proprietary data covering 25,000 games from 1,000 suppliers across 1000 operator sites.